Emily Dickinson, Dorothy Wordsworth, and the Poetics of Everyday Life

Olive Amdur ('23) on solitude, community, and the dailiness of creativity

Note: As ACP interns, we wanted to find new ways to engage students with Amherst College Press. We put out a call to the Amherst student body for submissions to our Community page; these submissions could have been any piece of writing that is inspired by or about the books that the press has published. Once we approved the proposal, we worked with the student to help with editing and suggestions for the piece. Now, we are excited to share our first student submission and look forward to submissions that follow.

-Sydney Ireland ('23) and Angel Musyimi ('23)

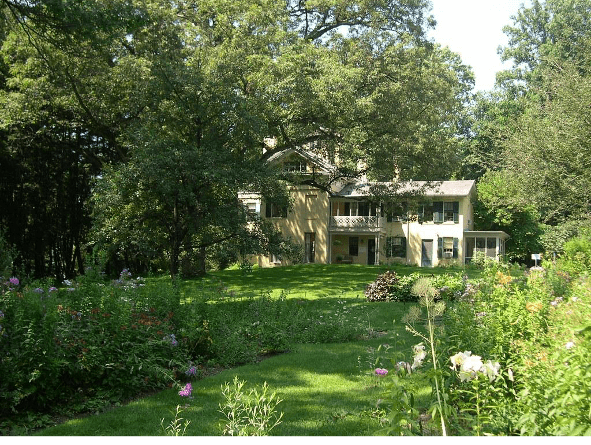

The house where Emily Dickinson spent her life sits, butter yellow and surrounded by thick trees, on a hill above the town of Amherst. In the early- and mid-19th century, when she lived, farmlands stretched down from the hill and towards the newly-founded college. She wrote at a wooden desk in an upstairs window, looking out over these lands: towards the round-topped mountains, the railroad line cutting through fields, the wooden houses and stone church steeples. Dickinson’s solitary reputation precedes her; she is the poet of the upstairs window, the poet whose work is saturated with lonely images, the poet who tells us, “I’m nobody!” She was also, however, a poet of letters, and of rich correspondence in and beyond Massachusetts. Dickinson lived at once in seclusion and community—in private and public—and this was, for her, the creative life, immersed in poetry, nature, and shared ideas.

Nearly half a century before and across an ocean from Dickinson, the poet Dorothy Wordsworth wrote meticulously by the stone fireplace of the English Lake District house she shared with her brother William. While William wrote stanzas, ballads, and odes, Dorothy kept rich and lyric journal entries, documenting the movements in and around their home each day. She slept in a back bedroom with newspaper plastered on the walls for insulation but wrote from a narrow table in the cottage’s main room, capturing in a few spare, strong lines every walk on the shores of Grasmere’s lake, every visit from Coleridge, every late night read aloud, and every day when rain prevented time outside and any inspiration at all.

Like Dickinson, she lived and wrote in the space between solitude and connection, and every day, from the heart of their home, Dorothy developed a poetry of located routine. For women, in the times when both of them lived, the home was a fraught space of enclosure and intimacy, of limitation and affection, and of daily proscription. Both Dorothy and Emily, however, wrote in this fraught space, and as we see them wrestle with this there emerges in their journal entries, notes, and letters a new poetics: one both defined by the solitude of home yet enmeshed in a liberating community beyond it.

In The Networked Recluse: The Connected World of Emily Dickinson, a collection of writings designed to accompany the Morgan Library's exhibition of Dickinson’s manuscripts and published by Amherst College Press, the stories of Dickinson’s solitude are explored and, in many ways, disrupted. As Carolyn Vega writes in The Networked Recluse, the places, people, and daily experiences described in Dickinson’s informal writings—her letters, her scribbled notes, her first poem drafts—place her into, “an extensive web of relationships to family, friends, and the literature and mass culture of her time.” In an 1845 letter to her brother Austin, Dickinson writes that, “If it is pleasant day after tomorrow we are all coming over to see you, but you must not think too much of our coming as it may rain and spoil all our plans.” Elsewhere there are mentions of visits to the college, attendances at musical performance, and countless times with friends—from home, from seminary, from town. Though far more bound by domestic expectations than her brother, it is Dickinson’s writing that carries her beyond the yellow house and down from that hill above Amherst’s fields and farmhouses. Her letters and manuscripts capture a life filled with people, places, activity, and conversation: a life filled with solitude and seclusion but deeply integrated in creative communities.

In Dorothy Wordsworth’s descriptions of her daily walks, visits, and practices of housekeeping, we see her similarly rooted in the communities of her home place. She writes in the opening entry of the Grasmere journal, “Wm & John set into Yorkshire after dinner at 1/2 past 2 o’clock—cold pork in their pockets. I left them at the turning of the Low-wood bay under the trees. My heart was so full that I could hardly speak.” We can picture her watching William and John leave for town, and imagine her overwhelmed with the joy of seeing them and the depth of nature all around. She takes note not only of the weather, the food eaten, and the change of seasons but of all the ways people move in and through the house: the visitors William Wordsworth (Wm) takes, the neighbors who stop by, the figures Dorothy meets on her walks. Later in this same entry she notes, “The crab coming out. Met a blind man driving a very large beautiful Bull & a cow—he walked with two sticks. Came home by Clappersgate. The valley very green.” Her poetic entries map the people and ideas of their home, their creative world. Dorothy was, from her table by the fireplace, an integral figure in this home, and her journals enable her to create a picture of this integrated web of artists, daily habits, and conversations from which poetry grew: from which she and William emerged as writers.

Emily Dickinson’s letters, collected in The Networked Recluse, work in a similar way. They draw out the habits and interactions that governed Dickinson’s experience, allowing us to see her not only in her solitude but in her community. We have access to her privately public, and publicly private, life of creativity. In another letter to Abiah, Emily describes, “At 6. oclock, we all rise. We breakfast at 7. Our study hours begin at 8. At 9 we all meet in Seminary Hall, for devotions. At 10¼ I recite a review of Ancient History.” She narrates her whole day like this, and though they may not read like her poetry, we see Emily in her environments through these writings: Emily at the breakfast table, Emily in the classroom, Emily at a different, earlier desk, working away.

Marta Werner, in her essay for the collection, “Emily Dickinson: Manuscripts, Maps, and a Poetics of Cartography,” charts the places and moments Dickinson captures in her writings. She explains, “‘Dickinson' cannot be a solipsistic set of meanings, but rather…a dazzlingly complex array of contexts, human and natural, and experiences.” By observing—mapping—her routines in the complex space of home, Emily Dickinson grounds her work in everyday feelings, encounters, and practices, as well as in the people who are part of them. Dorothy Wordsworth, in the same way, intertwines her poetry and careful schedule-keeping—her lyrical phrases and notes on keeping house—to position her work in its environment. Dorothy’s subtle poetry emerges from the garden, the kitchen, the fireside and the nature of their cold, close lake.

Dorothy and Emily, as poets in a time when women—white and class-privileged women—were bound to home routines and given voice almost exclusively in domestic spheres, reaffirm the power that extends from these routines, spaces, and communal processes of home. As they find poetry in the daily movements of home, Dickinson and Wordsworth establish their strong, singular voices and root those voices in their surrounding webs of art, intellect, and life. Their poetry allows for their “dazzlingly complex” environments to surface alongside their more solitary ones.

One of the essays in The Networked Recluse, a piece by Susan Howe, includes a fragment of a letter Howe’s aunt sent her in conversation about Dickinson. She writes, “[Dickinson] is the quintessence…of the Puritan descent....We conversed with our own souls till we lost the art of communicating with other people.” Yet in Dickinson’s letters we see her in conversation with her closest friends, the people of the farmlands surrounding her home, and the elements of her domestic life. We see her, too, in conversation with Dorothy Wordsworth, a conversation that carries us ahead in time and across an ocean, about the defiant poetry of everyday life. What we see, holding the subtle poetry of Dorothy’s journals with Dickinson’s manuscripts, is a new way of understanding poetic voice and practice: one at once solitary and constantly engaged with the world. They model holistic poetics, born of an environmental and interconnected daily creativity: a writing that, to echo Frost, another Amherst poet, may be alone but is not lonely.

Olive Amdur ('23) is a rising junior at Amherst College majoring in English and American Studies. She loves Romanticism, education, and literary criticism. Originally from Brooklyn, New York, she loves the city but has found a new, greener home in the Pioneer Valley too.