“Imagine a World”

ACP intern Evelyn Chi ('25) on zines as forms of resistance

Anyone can make a zine and publish it. Take a piece of printer paper, fold it into a booklet, draw on it, and voilà–you have a zine! Photocopy it, hand it to your friends, and now it’s published.

Zines are small, handmade magazines that contain art, collage, and photography alongside text relating to a specific theme or issue. They differ from traditional books, since creators self-publish zines and distribute them in limited quantities. As an extremely accessible and inexpensive art form, zines often represent non-mainstream and underground voices. Protest and resistance are vital to zine culture, which challenges the mainstream by resisting structures of power and dominant, centralized systems.

Throughout their history, zines have rebelled against issues like slavery, homophobia, racism, and sexism. In the 1830s, the American Anti-Slavery Society distributed wood-printed abolitionist pamphlets with speeches, sermons, and proceedings from their meetings. In the 1940s, the first queer fanzine, Vice Versa, was published by Edythe Edye, who was known by her pen name Lisa Ben (an anagram of “lesbian”). The punk rock movement in the 1980s and 1990s led to the creation of Riot Grrrl, an underground feminist group that created zines and songs addressing sexism in the punk scene. Today, collections like the POC Zine Project and Brown Recluse Zine Distro share zines made by Black, Indigenous and people of color, combining curation, community, and advocacy.

During my visit to Taiwan over winter break, I stumbled upon a charming little bookstore named Bleu & Book at Hua Shan Creative Park in Taipei. There, I discovered an entire collection of zines about the protests in Hong Kong. Their topics ranged from a summary of the protests titled, What happened in Hong Kong?(香港到底發生了什麼是?) to Let’s go picnic! with illustrations not of food and picnic blankets, but protest gear like gas masks, construction helmets, and heat-resistant gloves.

A zine with an entirely black cover, 出入口 , or Passages, captivated me. This zine was written primarily in English with Mandarin and Cantonese mixed in, reflecting the Cantonese-American identity of the author Liana Fu. Set in Hong Kong in 2019 at the height of the pro-democracy protests, Passages deals with Fu’s internal conflict as a diasporic writer, anger at police violence, feelings of loss towards Hong Kong's political precarity, and ultimately, questions about home and belonging.

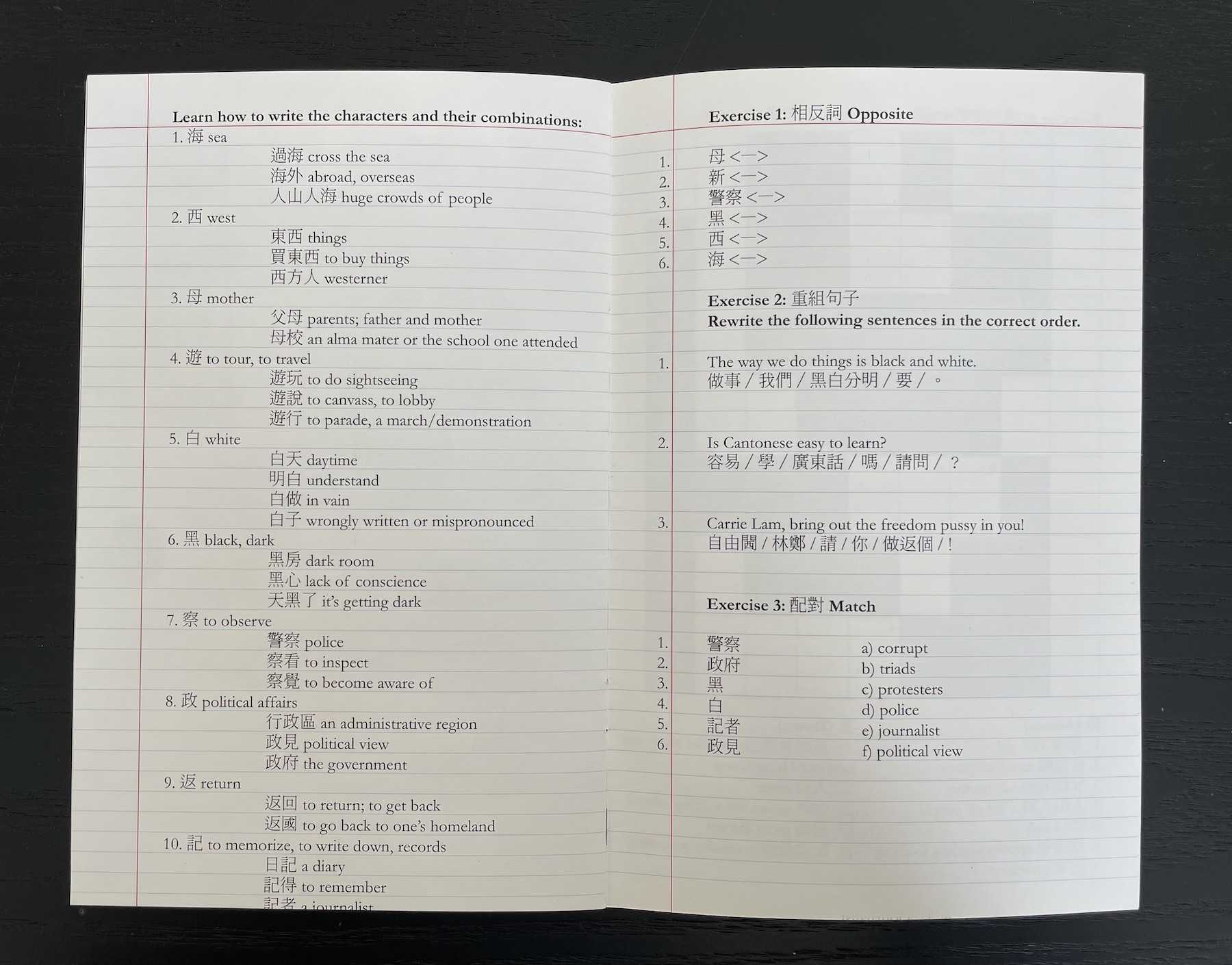

The zine weaves together prose, poetry, and mixed-media art. There are photographs taken by Fu, a crossword, and even a mock workbook section that replicates activities in Chinese workbooks. In the answer key at the end, Fu matches words from a workbook activity “incorrectly,” connecting “police” with “triads” and “government” with “corrupt.”

While reading Passages, I kept thinking about the spirit of resistance in zines. From the outset, Passages defies genre by freely switching between narrative forms, alternating from poetry to letters to diary entries. Embedded within Fu’s words are anger, loss, and a call for change. At the end of Passages, Fu writes in both Chinese and English: “解散警隊,全民自治”; “Abolish the police, self-governance for all.”

Just as their content challenges larger systems of oppression, zines’ circulation defies dominant, centralized, for-profit systems. Traditionally, zines are not made for profit. There are many digital zine collections today that anyone can freely access and download, such as the Queer Zine Archive Project, Small Science Collective, and Solidarity! Revolutionary Center and Radical Library. These digital collections share the goal of making zines and knowledge more accessible to marginalized communities.

By defying for-profit systems, zines are similar to open-access presses. Open-access presses publish books that readers can access completely free of charge. Unlike journals or newspapers that require subscription access, OA presses allow any reader, regardless of income, to access material. Platinum presses like Amherst College Press also do not charge authors or their institutions, further eliminating barriers to publishing. Like zines, OA presses are committed to sharing knowledge so that everyone can read and learn, creating spaces of equity and inclusion for all.

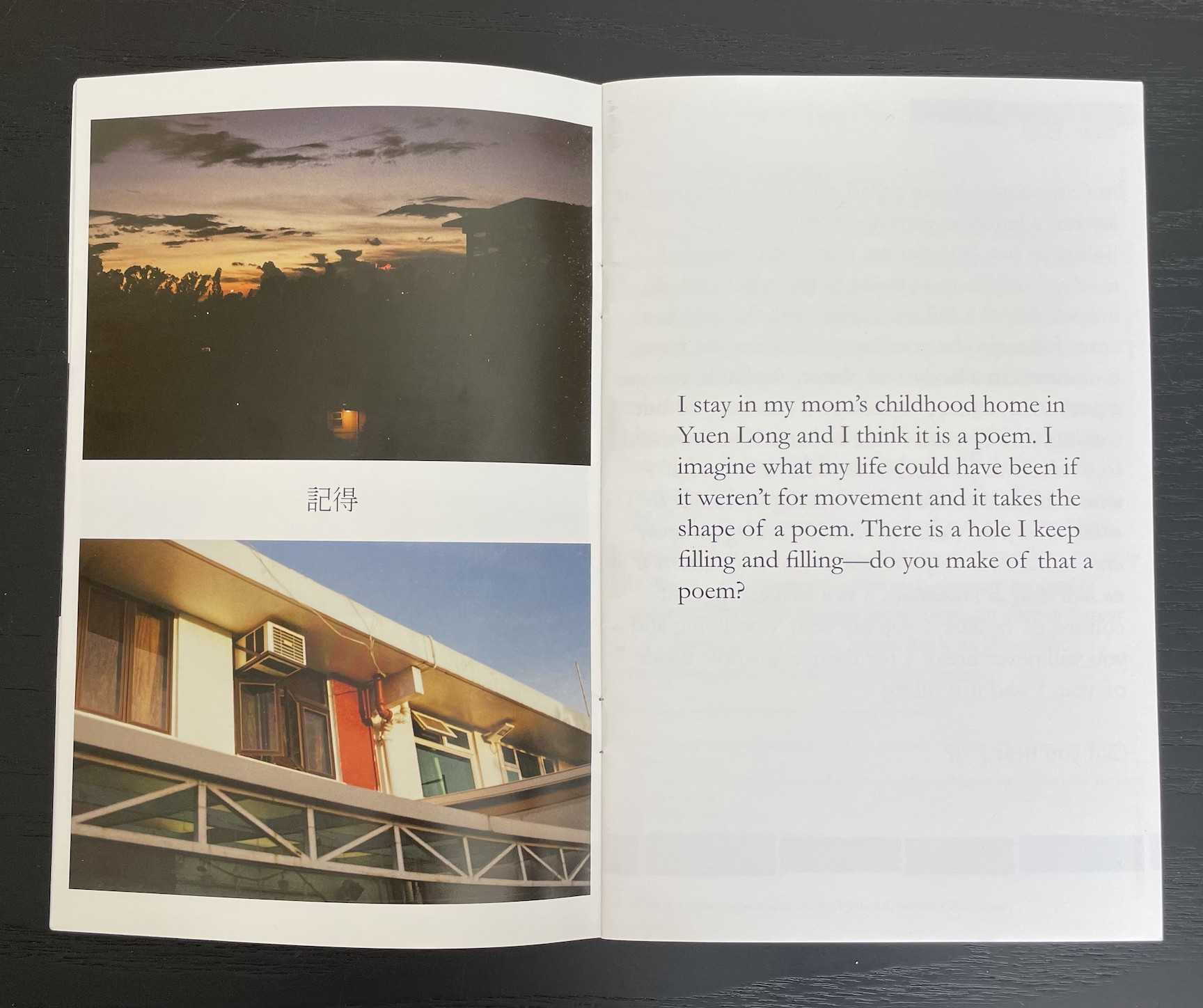

But perhaps equally important to the idea of resistance and open access in zines is the concept of intimacy. Passages feels deeply personal in a way that only a zine can. I feel intimately connected to Fu when I see the photographs of her mother’s apartment, or when I’m invited to write in the red-blue lined workbook section “Imagine a World.”

As a Taiwanese American, I share Fu’s anger towards Chinese hegemony, colonialism, and dictatorship. Like Hong Kong, Taiwan was colonized by many countries, including the Netherlands, Portugal, Japan, and now China. I feel Fu’s loss intimately when she states how she is in Hong Kong “on borrowed time in a borrowed place” – the feeling of being traded between colonizers and borrowed like money. For both of our countries, democracy feels elusive, almost impossible. When will we be truly free?

This is why Fu encourages me–encourages us–to “imagine a world”:

"What would this little border island of 7 million look like without China, without Britain, without America? Without capitalism, without class inequality? Without police? The struggle, the work, the obligation and duty of this borrowed place is to create itself–imagine itself."

* I want to give a big shout out to Frost Research and Instruction librarian and zine expert Alana Kumbier for helping me research and find sources about zines. Thank you!

Evelyn is a sophomore English and Sexuality, Women’s, and Gender Studies double major from Los Angeles. She is interested in postcolonial literature, Asian American writers, and intersectionality. Outside of class, she likes playing piano, baking cookies, and drinking good matcha lattes.